Cover

Black CPA Centennial celebrates first Black CPA

Issue 3

July 19, 2021

By Anita Dennis

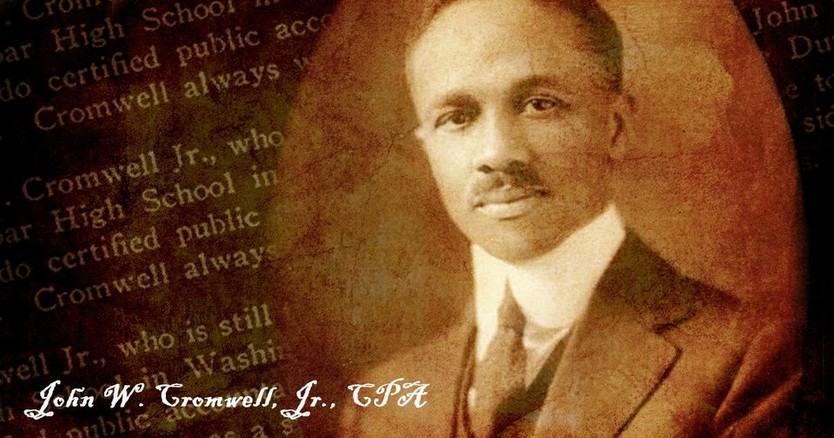

John W. Cromwell, Jr., the son of a former slave, overcame many obstacles in his life to earn his place in history as the nation’s first Black CPA in 1921. His story is an inspiration and lesson in tenacity for future generations of Black accountants.

John Wesley Cromwell, Jr. (1883–1971) was a man of many talents and interests. An intellectual with a passion for knowledge and a drive for opportunity, he was the nation’s first Black CPA. Cromwell earned that distinction in 1921, an achievement that is the starting point for this year’s Black CPA Centennial celebration.

Cromwell was well suited for his historic role. Like many pioneering CPAs of color, Cromwell overcame numerous obstacles to reach his goal, paving the way for generations of future Black accountants.

“African-Americans struggled against incredible barriers in order to become CPAs and were virtually invisible,” said Theresa A. Hammond, CPA, Ph.D., accounting professor at San Francisco State University’s Lam Family College of Business.

The first CPA law was passed in New York 1896. It would be another 25 years before a Black person joined the profession. The primary blockers that made licensure essentially impossible for many aspiring Black CPAs included education, experience, and exclusion.

A family of educated achievers

Cromwell graduated from college in 1906. While most Americans did not attend college at that time, only 1 in 3,600 Blacks had a college degree and whites were five times more likely than Blacks to go to college, according to Hammond’s book, A White-Collar Profession: African-American Certified Public Accountants Since 1921. A combination of factors, including denial of or obstacles to education during and after slavery, fed this outcome.

Cromwell’s father was born a slave in Virginia. After his family purchased their freedom, Cromwell Sr. ultimately graduated from Howard University law school. At different points in his life, Cromwell Sr. worked as an attorney, teacher, and activist. He founded newspapers, contributed to journals, and was a leading scholar of African-American history. He also served as the chief examiner of the U.S. Postal Service and argued cases before the Interstate Commerce Commission.

The younger Cromwell attended a college preparatory program at Howard and studied mathematics and astronomy at Dartmouth College, earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees, graduating Phi Beta Kappa, and winning the Thayer Prize in mathematics there.

Work experience for licensure proved impossible

Cromwell, who taught himself accounting, was initially prevented from qualifying for a CPA license because of a common challenge for Blacks at the time: Most states required CPA Exam candidates to work for a licensed CPA at an accounting firm. While Cromwell and numerous other Black aspiring CPAs in much of the early 20th century attempted to find jobs that would give them the experience they needed, firms generally refused to hire them, insisting that their white clients would not be comfortable having their work handled by a Black person.

Faced with this seemingly insurmountable hurdle, when Cromwell left college, he returned to his hometown of Washington, D.C., teaching mathematics at Paul Laurence Dunbar High School, a prestigious Black high school.

Tenacity pays off

Fortunately, Cromwell was ultimately able to do an end run around the obstacles that had blocked him from becoming a CPA. In 1921, when New Hampshire dropped its experience requirement, he finally could take the Uniform CPA Examination and become a CPA. It had taken him 15 years from the time of his graduation to gain the chance to become licensed. He continued to teach and spent three years as the comptroller of Howard.

“Pioneers cause change because of the strength of their character,” said Gary Previts, CPA, Ph.D., co-author of A History of Accountancy in the United States and E. Mandell de Windt Professor of Leadership and Enterprise Development and professor of Accountancy, Case Western Reserve University.

During the time that Cromwell was a CPA and teaching, he also performed accounting services for a variety of businesses in the Black community. Washington, D.C., had several thriving Black neighborhoods filled with Black-owned businesses. The U Street area, which was known in the first half of the 20th century as “Black Broadway,” featured Black-owned restaurants, the popular Whitelaw Hotel, clubs, mom-and-pop stores, YMCAs, and churches, as well as the largest Black-owned bank in the country. In addition, the Georgetown neighborhood was 30 percent Black in 1930, with a strong local community.

Cromwell’s legacy lives on

Cromwell is an inspiring figure as much today as he was yesterday. Previts pointed to a recent example of the ongoing recognition of Blacks in the profession: William Louis Campfield, CPA, in 2019 was the first Black accountant inducted into the Accounting Hall of Fame. Campfield was the grandson of slaves. “There is reason to be hopeful that these kinds of positive changes will continue,” Previts said.

“Seeing the struggles that early Black CPAs like Cromwell overcame should be a motivating factor for subsequent generations,” said Frank Ross, CPA, a visiting professor and the director of Howard University School of Business Center for Accounting Education. “The more I learned about him, the more I wanted to work as hard as I could to accomplish what I can in this profession,” added Ross, who was one of the nation’s first Black partners at a major accounting firm and is a co-founder of the National Association of Black Accountants.

Hear more from Hammond and Ross, and others, in the Black CPA Centennial podcasts at kycpa.org/DI.

About the author: Anita Dennis is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

The Black CPA Centennial is a yearlong effort to honor, celebrate, and build upon the progress Black CPAs have made in shaping the accounting profession.